Importance of Traditional Indigenous Education

🌱 1. Generational Knowledge & Sustainability

- Traditional drying methods (like sun-drying, smoke-drying, or air-drying) are eco-friendly and don’t rely on electricity.

- Techniques are based on local climate, geography, and seasonal rhythms, passed down orally or through hands-on teaching.

✅ Learning these ways means preserving both food and culture sustainably.

🔥 2. Deep Understanding of Ingredients

For example:

- Drying berries like Saskatoon berries or chokecherries involves specific techniques to retain nutrients and flavor.

- Drying fish or game meat requires knowing the right temperature, smoke type, and timing—skills honed over centuries.

📚 This kind of education isn’t found in textbooks—it’s lived experience.

🌎 3. Food Sovereignty & Cultural Resilience

- Teaching drying methods strengthens community health by reducing reliance on store-bought, processed foods.

- It also revives ceremonial and communal aspects of food prep, like group harvests or seasonal gatherings.

💬 “Drying food” isn’t just a task—it’s a story, a celebration, and a way of remembering who you are.

🧒🏽 4. Empowering Youth & Reviving Languages

- They gain practical survival skills and cultural pride.

- They often learn in Indigenous languages, reinforcing linguistic identity.

- It builds intergenerational connections—elders become teachers, and youth become stewards of tradition.

👣 It’s a way to walk in two worlds—honoring the past while building a strong future.

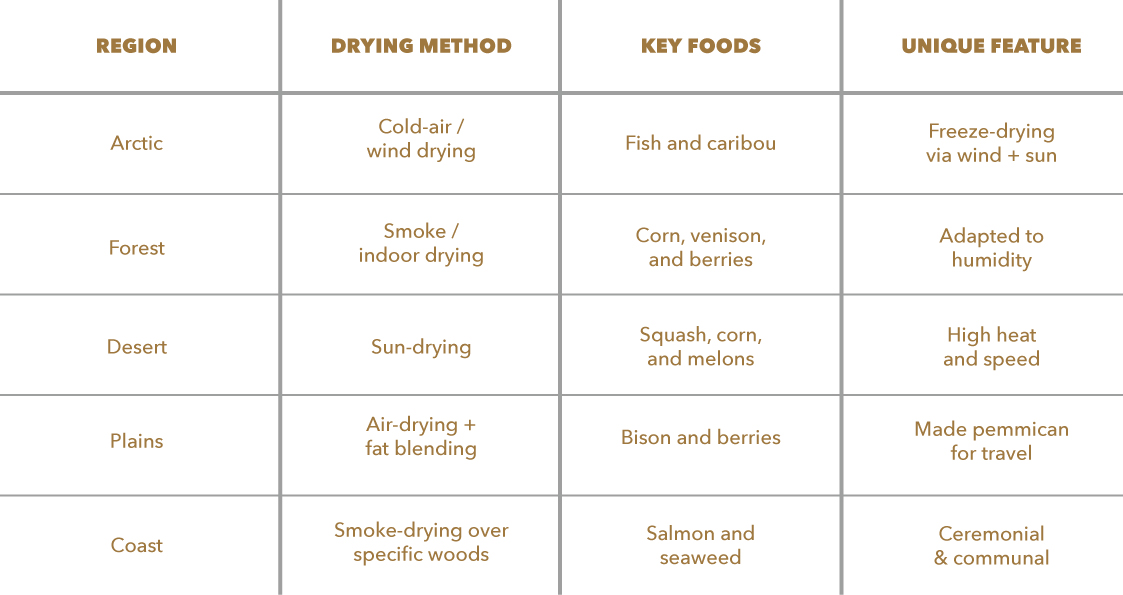

The food-drying practices of Indigenous communities vary widely depending on geography, climate, available resources, and cultural traditions. Here’s a breakdown of how these processes differ across regions and nations, with a few standout examples:

🏔️ Arctic & Subarctic Regions (e.g., Inuit, Dene, Gwich’in)

❄️ Cold-Air & Wind Drying

- Climate Adaptation: In cold climates, drying happens using wind and cold air rather than heat.

- Foods Dried: Arctic char, caribou, whitefish, and sometimes berries like cloudberries.

- Method: Strips of fish or meat are hung on drying racks outside, sometimes lightly smoked.

- Example: Inuit communities often dry fish in spring when temperatures are below freezing but the sun is strong—ideal for low-moisture, high-protein dried food.

🧊 Drying in cold air prevents spoilage without salt or refrigeration—a survival method rooted in deep knowledge of seasonal shifts.

🌲 Woodland/Forest Regions (e.g., Anishinaabe, Cree, Haudenosaunee)

🔥 Smoke-Drying & Indoor Methods

- Climate Adaptation: Frequent rain and forest humidity mean that open-air drying isn’t reliable.

- Foods Dried: Corn, venison (jerky), berries, and mushrooms.

- Method: Foods are dried near low fires in smokehouses or inside lodges over long periods.

- Example: Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) dried “Three Sisters” crops (corn, beans, squash) for winter storage.

🌽 Smoke not only dries but also preserves food and adds antimicrobial properties—an ingenious blend of food safety and flavour.

🌵 Desert & Plateau Regions (e.g., Navajo/Diné, Hopi, Ute)

☀️ Sun-Drying on Rocks or Rooftops

- Climate Adaptation: Arid conditions allow effective sun-drying outdoors.

- Foods Dried: Corn, squash, beans, melons, and wild plants like amaranth.

- Method: Foods were traditionally sliced and placed on rooftops or flat rocks, with drying occurring rapidly.

- Example: The Hopi dried thin slices of squash to make “squash chips” for soups or stews.

🔥 Intense sun made it possible to preserve food quickly—essential for food security in a harsh environment.

🌾 Plains Nations (e.g., Lakota, Blackfoot, Cheyenne)

🛖 Air-Drying Meat for Pemmican

- Foods Dried: Bison meat, berries (especially chokecherries and Saskatoons).

- Method: Meat was dried into thin strips and combined with dried berries and fat to make pemmican, a high-energy survival food.

- Storage: Often wrapped in hide or bark for long journeys or winter.

🥩 Pemmican is one of the most nutrient-dense, long-lasting foods in the world—an innovation from Plains cultures.

🏞️ Pacific Northwest (e.g., Coast Salish, Tlingit, Nuu-chah-nulth)

🌫️ Smoke-Drying Over Cedar Fires

- Foods Dried: Salmon, eulachon, seaweed, roots like camas.

- Method: Fish are split, cleaned, and hung in smokehouses, using specific woods (like alder or cedar) to enhance flavour and preservation.

- Cultural Practice: Salmon drying is often part of a larger seasonal round, with community and ceremony tied into the process.

🐟 Salmon drying is not just about preservation—it’s a deeply sacred act connected to gratitude and reciprocity with nature.